Penrhyn Life Part 3 - Fishing

On Penrhyn Island you only put your baited hook in the water when you can see the fish you want to catch. I was much impressed. Maru could see the look on my face, amazement turned to excitement as I pulled up a nice ruhi (black trevally), then another, and another. He questioned me.

“So in Australia, you just drop your line in the water, then sit there and wait?”

“Err yes, thats right”, I said rather embarrassingly. It sounded a bit futile when put so bluntly. I much prefer the Island way.

From the very first Polynesian settlers that made their way to Tongareva Henua (Penrhyn Island) all those years ago, right up to the present day, fishing has played an integral role in Island Life. Although the techniques have changed somewhat, and the boats too, still much remains the same. Here the lagoon and fringing coral reefs abound with fish, just as they always have, and to catch these fish there are numerous different techniques employing a range of traditional and modern equipment. We’ll focus on three common techniques; pole fishing, trolling, and spearing, as well as mentioning a few others.

But first, we’ll start by describing the boats, as just about every adult male here has one, and they are an essential to Penrhyn life. They are almost exclusively aluminium dinghies (skiffs/tinnies) in the 14 to 16 foot range, they are powered by outboard motors (mostly Yamahas) between 15 to 40 horsepower. These boats sit on the beach and are taken in and out of the water by hand, each day. The boats are all very clean and look near new; for this reason I assumed that they must have a short life and be replaced often. How wrong I was. Some of these boats are over 30 years old, and are constructed with a combination of welding and rivets; a clear indication of age. Up until now I haven’t had a whole lot of respect for aluminium as a boatbuilding material. All the tinnies my school friends and I owned as teenagers seemed to crack, corrode and leak; and were never easy to repair. I now find myself surrounded by aluminium boats, and very much appreciating them. I really am astounded at how long they last and in what good condition they are kept. I guess it just goes to show how important good care is. You may wonder however, just as I did, what happens when the hulls do eventually crack, how they are repaired? Well, as luck would have it, there happens to be the wreckage of a WWII B-24 bomber amongst the cemetery, providing an endless supply of aluminium for patching dinghies. Isolation breeds resourcefulness.

Here the men go fishing many times a week, always in the early mornings or late afternoon. You’ll almost never see a dinghy go out during the middle of the day, mostly because the men have jobs to do, but also because it would be much too hot. Most men go out with a mate or two, and some go alone. I’ve been lucky enough to go out fishing a few times and so, from my recollections, I will take you, the reader, along for the ride. This sort of vicarious fishing is well suited to the armchair explorer. I’ll make certain we catch a few fish, and if I’m feeling generous, it might even be a calm day when we head out. But, before we go any further, we must start with a fisherman’s prayer, out of respect, but also, I would hate to diminish our chances of a good catch. This prayer is said before the fishing begins, and is always an impromptu yet sincere devotion.

To matou metua ite ao, teia matou I rotopu iakoe e ore atu nei matou iakoe te Atua, e akamanuia koe ia matou ite ki o te moana. Te rakua nei ia matou ite akahoki atu I ta matou akameitakihanga kia koe te Atua no tei tiaki koe ia matou e, e Atua aroha koe ete Atua hinangaroia. Te Atua e, te pure atu nei matou kiakoe e to matou Atua,e akakii koe ia matou ki tu hua o te ika, kua kite matou e, e au tamariki hara matou, te ore atu nei matou e te Atua akakore mai koe I te reira, I roto I te ingoa o tau tamaiti ko Iesu mesia matou I pure atu ai.

Amene.

We’re up early this morning, 4:45. There’s still no hint of daylight as we get dressed, put our knife and sheath in our pocket, don our head torch and jump on our bike, still half asleep. It’s a 60 second ride to Maru’s house, we arrive at one minute past five. “Here, take a seat, we’ll go at 5:30” he says calmly. There we sit, in the darkness, chatting quietly about the morning ahead. Before long it’s time to go. We grab the fuel tank, the trolling lines, two knives and two short rods; everything we need for a morning of fishing. We walk the 150 metres from Maru’s house to the lagoon side beach. The fuel tank is connected, the rods are stowed, and we push the boat, with ease, down the two pvc pipe skids and into the lagoon. We hold the boat in thigh-deep water, the outboard is started, and we jump in. Maru puts the motor in reverse, and expertly weaves amongst the coral heads and into the deep, all the while the short sharp waves are slapping in over the transom. Once clear of the shallows we turn around and make straight for the western pass, Taruia. Once we get up to speed, the bung is removed and the water inside drains out. It’s about three kilometres to the pass, it doesn’t take long. As we make our way there the first hints of daylight are visible, a purple glow in the east appears, and before too long we are enveloped by the early morning light. We’re the first boat out, but can see the lights on the beach of others getting ready. Once through the pass, we make a sharp left, and sit just off the coral reef next to the pass. At this moment the outboard is turned off, and we begin to drift. It’s time for the prayer. We close our eyes, bow our heads, and Maru begins. There’s something chant-like in the way he repeats this devotion. I must admit, at this point, although supposedly deep in prayer, I tend to keep one eye open. The waves crashing on the reef just metres away, and our lack of propulsion, makes me slightly nervous.

As soon as the prayer is said the motor is started and I’m ready with the anchor. On the signal I drop it into the clear water and it bites onto the coral. Maru begins to chop up some fish into small chunks, this will be berley and bait. I grab one of the rods, a stiff three foot hardwood branch with a line of equal length tied to the tip. On the end of the line is a small hook. Maru is leaning over the side, massaging the berley in his hand, watching the trail of meat drift away. Sharks appear, as they always do on Penrhyn. “Don’t put your line in the water until I say.” Then, a few minutes later, we see the ruhi (black trevally) appear. “Now”. I drop my baited hook in the water and then, a few seconds later, a healthy fish is hanging from my rod. We both whoop and cheer as it lands in the boat. We continue on in this fashion, Maru eventually picks up his rod too, and we’re both pulling in nice fish. I would have thought that after a lifetime of fishing, the thrill would wear off, but I was wrong, we both show equal enthusiasm for the task. Our shouts can be heard by the three other boats that are now in our vicinity, we’re all chasing the same fish. We have to be careful though, as the troublesome sharks can easily bite through the line, taking our precious hooks. For this reason we are constantly pulling our short lines out of the water as a shark approaches. The morning went well, we’ve got almost a dozen nice fish in the bucket. As the sun starts to peek over the tops of the coconut palms on the eastern side of the lagoon, the fish stop biting, and it's time to start trolling.

We stow our rods, up the anchor, and begin heading north. On each side of the dinghy, tied around the forward thwart, are short ropes with a stainless steel clip at one end and an inner tube acting as a shock cord in the middle, onto these clips are attached long lengths of small diameter polyester line with a large swivel and heavy leader. On the end of one line we have a plastic squid jig, and on the other is a simple, hand carved ironwood lure. We both don our gloves and begin heading for the waters that stretch north-west off Siki Rangi pass. We are accompanied by four other boats; yesterday some large schools of bait fish were sighted, everyone’s keen to catch a fish. We’re hoping for tuna, but could also get wahoo, mackerel, rainbow runner, or others. Trolling is an enjoyable yet costly way to fish. Fuel is much more expensive than it once was, and so the days of chasing schools of tuna for miles off the island are now gone, a morning of trolling may use half a tank of fuel, or more, and unless a nice sized tuna is caught, it turns into an expensive and futile exercise. The stakes are high. As we troll, at speed, we remain silent, keeping our eyes on the lines, waiting for the inner tube to stretch, signifying that a fish is on. We keep a close eye on the other boats too, we see one haul in a nice fish, the others aren’t as lucky. Then we see it, a big flock of birds to the south, everyone turns and heads that way, heading for the tuna. We spend the next hour chasing the schools of birds, who are chasing the schools of bait fish that are being chased by the tuna, that are being chased by us, along with half a dozen other boats, there’s excitement in the air as outboard motors rev and we all dart about eagerly. Eventually it happens, our luck turns. Bang. The inner tube stretches and there’s a big splash. “We’re on”. Maru begins to pull in his line with strength and gusto, for a moment I watch on in amazement. Then all of a sudden, I feel my line go tight, a fish is on! I stand up and begin to pull hard, it’s a true thrill. We have to get our fish into the boat before the sharks come. I pull and pull and eventually a big tuna is by the boat, then with a mighty heave it’s flapping around at my feet. Once again we whoop and cheer. We know all the other boats have just seen our good fortune. As we head back, passing the others, Maru makes sure that I stretch my hands out as wide as possible, showing the other fishermen the size of the tuna we caught. It’s all good fun out here, and one can never trust the answer when inquiring about another boat's luck.

Spearing is another common technique on Penrhyn. It takes the form of either a hand spear while walking on the reef, or a spear gun while swimming. The hand spears are usually long wooden poles with a multi pronged steel point, lashed to the shaft with steel wire. There is nothing simpler than waking in the morning, grabbing a spear and a bucket, and wading along the western reef, getting a good feed of uhu (parrot fish). Amongst the young men here, spearfishing with spearguns and snorkels is a popular sport, and it provides one with the opportunity to catch a large range of fish, and stock up the freezer at home. One morning, before there was to be a feast, I saw the island work barge head out with all the young men of the village. They came back a few hours later with enough fish to feed everybody, mostly uhu and succutoto (red tail).

I will briefly mention net fishing. I am yet to try it, so have little to say, but it seems to be a common and productive method. From what I understand, the numerous saltwater ponds around the island are the best place for netting. You see, these ponds are hand stocked with ava (milk fish) eggs, and are left until the fish reach maturity, they are then sustainably netted. Different families here lay claim to different ponds, and one must make sure they are not caught fishing in the wrong pond!

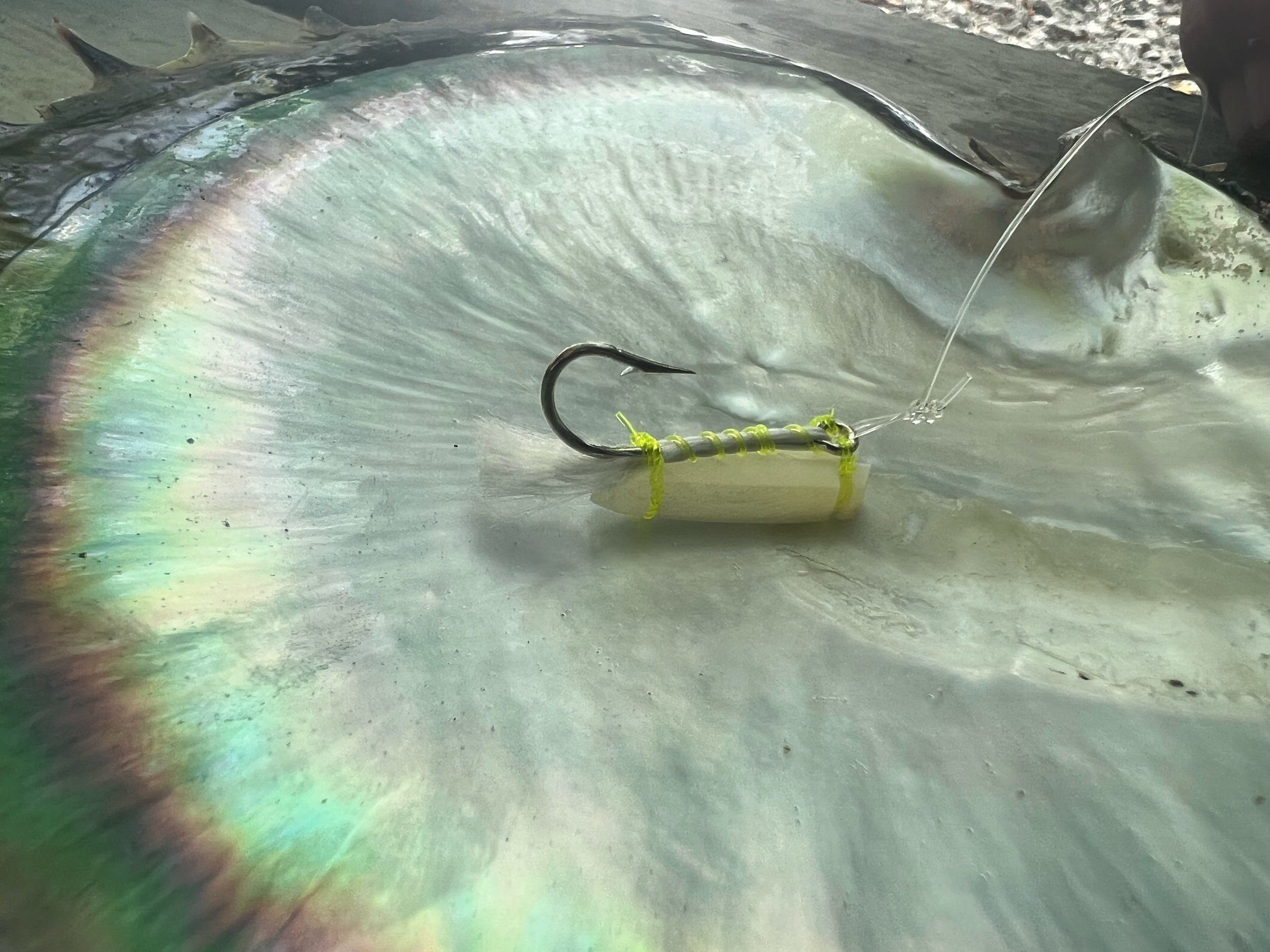

I had better mention the other form of pole fishing common on Penrhyn. It involves long (14ft +) rods, either manufactured graphite or bamboo, and a small handmade lure. There is no reel, the line attached on the end of the rod is no longer than the rod itself. At the other end is tied a wonderful little handmade lure. The body is carved from pearl shell, and a small tuft of nylon and a hook are attached, this is all done expertly with light fishing line. This setup can be used in many shallow water reef applications to catch a range of different species. The most impressive pole fishing I have witnessed is the fishing off the reef on the outside of the northern motus. Once again, I was with Maru, as well as his mate Sam. From our camping spot on the lagoon side of the motu we traipsed through the coconut groves and onto the exposed northern beach. Maru and Sam both had head torches, a rod each, and buckets made from old water containers slung across their shoulders. Both men had boots on. By the time we got to the beach, the sun was beginning to sink, Sam went one way, Maru the other. They mounted the sharp rocks and began to cast. With a seemingly effortless dexterity the lure is trailed in the water, flicked in the air, and cast back out again, in a fluid, circular motion that is a joy to watch. Every few casts a fish is hooked, the rod is brought to a vertical position, and the fish swings into the fisherman’s spare hand, in a second it’s in the bucket and the lure is back in the water. The real skill lies in the ability to be continuously moving along the rocks, never staying in one place for more than a few casts, navigating the rough terrain in the fading light. I was without a rod, but enjoyed following along, slowing beachcombing as I walked. It soon became dark and the bucket was almost full. Maru and I sat on the beach, cross legged, and waited for Sam. In low tones we swapped stories of the sea and of fish, gazing out at the vast, homely Pacific.

With all this fishing, I should expect that you’ve worked up quite the appetite by now, just as I have. Well, we arrived just in time to Maru’s house, and are shown to a seat at the table. His wife, Sila, is cooking the rice and tomatoes, and Maru is boiling the ruhi; they have been chopped in half and thrown into the pot. In a moment all is ready, and we sit down to eat. I load my plate up with rice and coconut sauce, Maru picks up the head of a fish and puts it on my plate. “This is the one you caught”, he says wryly. I said “It must be, as I caught all the fish!”. It pays to have a sense of humour in Polynesia. Of course, there is no cutlery, and we happily eat our dinner with our fingers, a much better way to consume a bony fish than with such clumsy utensils as a knife and fork. The truth is, I’m starving and for this reason I suck every fibre of meat from those bones, even the eyes are fished out with my fingers and devoured. Maru is much impressed. “You eat the eye of the fish you caught, you are a man now”. I smile heartily. He dishes me another half of a fish, this time it’s the body, I eat as much as I can while maintaining decorum. As soon as the meal is finished, I am handed a bag with a few tomatoes, and sent on my way.

I rode home through the darkness that night, contemplating the rather convoluted yet no less sincere way my father would teach economics at a university to ensure we could have fish for dinner once a week. What a pleasure it is to explore the many modes of putting food on the table.