Penrhyn Island - “Paradise under the Sun”

Part I

Yesterday I found myself lounging under the shade of a tin and driftwood shack, a Penrhyn ‘weekender’, the steady breeze rustling the coconut palms and taking the edge off another warm, tropical noon. I had just woken from a rather pleasant nap when all of a sudden I was met with a roaring appetite. I looked out over the azure lagoon. ‘Well’, I thought to myself ‘I could really go for one of those fried ava’. A second later, one of the women walked into the shack with a basket full of fresh ava (milk fish). The men had just come back from fishing. “Mahuta,” she said to me, “would you like your fish raw or fried?” Such is the warmth and hospitality of the Penrhyn Islanders.

So, how did I find myself in this situation? After five months at sea I was homing in on a tiny speck in the vast Pacific. I had no charts of the island, my only information was a brief description in the Pilot Book, and a rough sketch in a 1994 cruising guide that had been gifted to me on the eve of my departure. I learnt there was a village - the island must be inhabited - this was the vital information I needed. I then began to wonder: How many people would live there? What would they be like? Was there a resort? A hotel? A library? A grocer? Would the lagoon be full of visiting yachts? Would there be anything at all? Would I be welcome to stay? These were all questions I could not answer. I would just have to find out for myself.

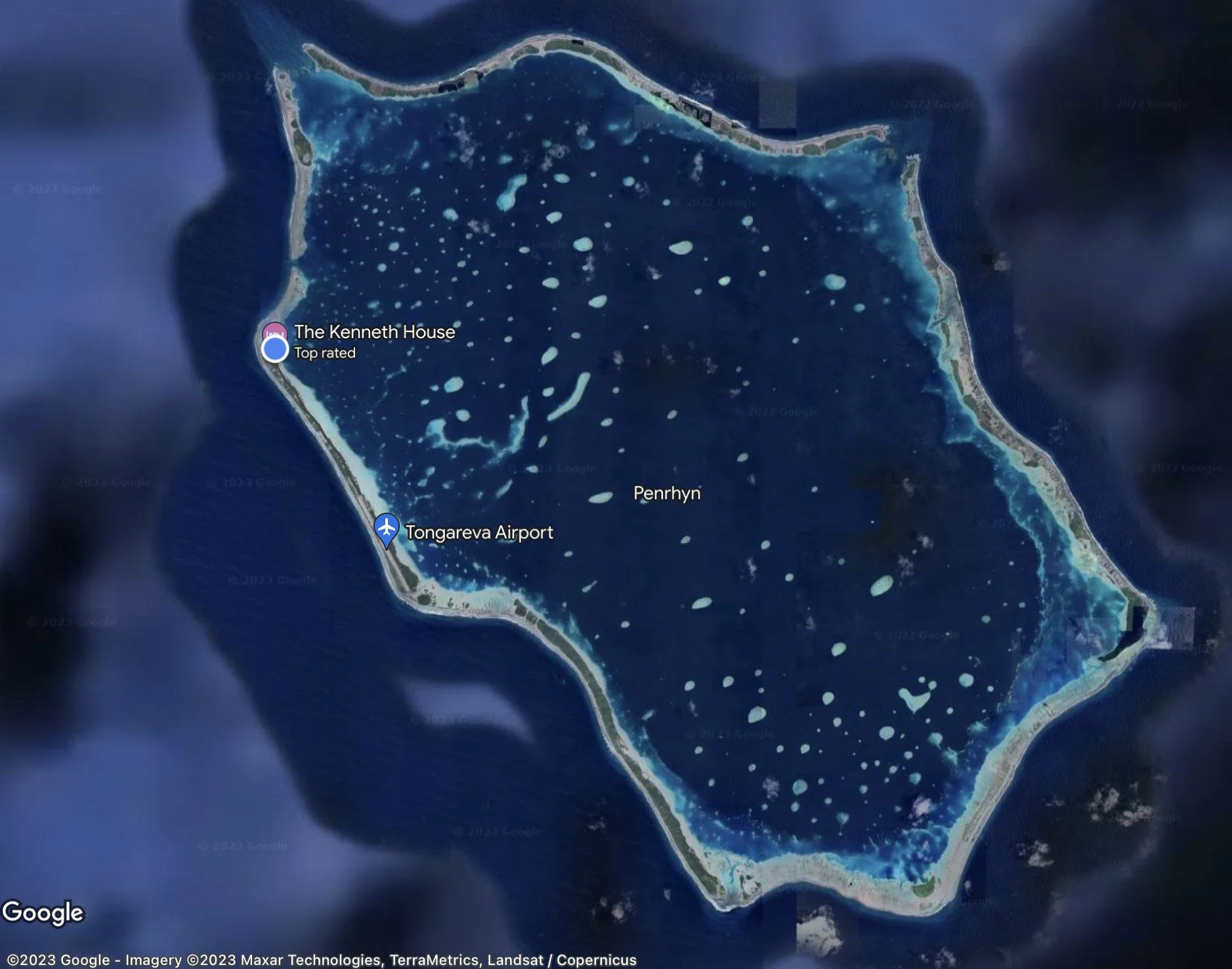

Penrhyn Island, also commonly known as Tongareva, is a large coral atoll in the North Cook Islands group. It’s the most isolated of the Cooks, as well as the largest atoll in the group. Rarotonga, the nation’s capital, lies over 700 nautical miles (1,300 km) to the south. Penrhyn got her name from the First Fleet ship, the “Lady Penrhyn”, when, in 1788, after delivering the first convicts to my homeland of Australia, her crew sighted the atoll, becoming the first Europeans ever to do so. For the next 66 years the people of Tongareva continued to live an isolated, unadulterated and hardy existence. Very few ships would have visited during this period, and the ones that did would have been met by a proud people who were often competing with rival chiefdoms on opposing motus for their livelihoods. It all began to slowly change when, in 1854, the London Missionary Society (LMS) sent three Polynesian missionaries to the island. From then, up to the present day, the LMS - now operating independently as the Cook Islands Christian Church (CICC) - has had a fundamental and profound effect on the lives of the inhabitants.

The next massive change to Penrhyn Island came in the early 1860s, when a Spanish/Peruvian blackbirding slave-ship visited the island, devastating the population by carrying away hundreds of inhabitants who would never see their home again. The ship eventually reached the port of Callao in Peru, the same port I left 160 years after their arrival (thankfully, no hard feelings are associated with Callao, something I was relieved about when filling out the customs paperwork). Since then, life on Tongareva has moved at a graceful pace, keeping up with modern technologies and eventually finding itself in the 21st century. Copra was once harvested, and pearl farming had a short but prosperous run here in the new millennium. Nowadays, the people still catch their own food, feed their pigs, harvest from the garden, weave hats, sing and dance. Many of the locals are now government employees, paid to keep everything on the island running smoothly - from the marine department, to agriculture, the building team, the power division, and on it goes. Everyone is kept busy. The fruits of their labour allow the purchase of necessities such as rice, flour, tinned beef, and fuel for their bikes and outboard motors.

Part II

When I finally neared Penrhyn Island and could make out the green tops of the coconut palms, I was met by the island work barge (a large aluminium punt with two great outboard motors), and a boat full of jolly people. With my biggest smile, I threw them my heaviest line (purchased specifically for this eventuality), and was towed through the dangerous Takuua pass on the eastern side; this was my first taste of land in over five months. I greedily feasted my eyes and imagination on what was a sensory overload of natural beauty: vegetation, sandy beaches and shallow, crystal-clear water. Truly breathtaking. We passed a family heading the other way in their aluminium dinghy, bamboo fishing rods hanging over the stern. They waved at me with enthusiasm and grace. The tow continued past the eastern village, Tetautua, where many of the locals came out of their houses to wave as we went past; instantly I realised that this was going to be a special place.

As we turned west and started to make our way across the 8 miles of open lagoon to the main village, I stared in wonder at the ten or so Cook Islanders who had come aboard the barge for the journey. The crew included the mayor, deputy mayor, police officer, customs officer, the school principal and her husband, and a few other important men of the village. These were the first people I had studied up close since my brief encounter with the Ecuadorians on Day 49. I was smitten. Surely there is no race more graceful, cool and jovial than the Cook Islanders.

The sun sank below the horizon, the tow line was let go, and I rowed the last few metres to the coral wharf where I was thrown a line. After my passport was stamped, I was given the go-ahead to step ashore. I stood in Maiwar’s tender cockpit, looking cautiously at the immovable, solid wharf. My mind raced, trying to calculate my first big step in over five months; then, with a purposeful leap I successfully made it onto dry land. I staggered a few paces like a drunkard, then was held upright between two mighty sentinels. I shook many hands and smiled for many photographs, it was all very overwhelming.

After the smiles and photographs, I was informed, very seriously, that I had a new name now. I was no longer Tom. I was now ‘Mahuta-hoehoe-asanga’. They explained that Mahuta was a famous warrior from the pagan times who came through the western pass on his canoe, hoe is ‘paddle’, and asanga is ‘from afar’. “This is your Penrhyn name now, my friend.” I stood there in awe and appreciation. I’m one of the very few outsiders to get a Penrhyn name, something I will have for life. I had read in old books about the odd adventurer getting a local name in Polynesia, always very personal and fitting. So, to know that this tradition still existed, and to receive one myself, was truly amazing. I now go by the shortened ‘Mahuta’.

Part III

As soon as I arrived, I realised just how isolated, small and traditional it is here. Even now, a month after setting foot ashore, every day I am impressed by a new aspect of Penrhyn life. Just about every warm, friendly, good natured and romantic stereotype I harboured about the Polynesians has been well and truly fulfilled. My nights are often accompanied by the sounds of ukuleles being played, singing and drumming, and from my window I can see the girls practising their organised hula dancing. The mummas, while weaving coconut fibre hats, look on with a critical eye and throw their hands in the air as example. Fantastic stuff.

The supply ship comes only a handful of times each year, a seven seater plane is chartered once or twice a month (at great expense), and we are well and truly out of the usual route for cruising boats. This means that tourism is unheard of, and any outsider who does manage to step ashore is treated very well by the 220 or so friendly inhabitants. As mentioned, there are two villages here. Omoka, the main village, lies on the western side of the lagoon, and is home to about 190 people, many of whom are children. It has two churches, a school, mission hall, community centre, Sunday school, ‘bank’ and one ‘shop’ – which is a very small room in a Papa’s home that has tinned goods and other essentials. As the lagoon is very large, Omoka is blessed by being exposed to the steady trade winds from the east. The constant breeze means that it’s very rarely too hot, the coconut palms are always rustling, and the flies are kept at bay. It all makes for the most pleasant of sites for a small settlement. The second village, Tetautua, lies directly opposite Omoka, on the eastern side. It is home to about 30 inhabitants and it too has many buildings including a school, church, Sunday school and community centre. Here the lagoon-side beach, being protected from the trade winds, is calm and crystal clear: Idyllic is an understatement.

The Cook Islanders are a surprisingly worldly bunch. They reap the benefits of their strong ties to New Zealand and use their NZ passports to travel freely here, there and in Australia. A few days ago I was chatting to a wiry old fellow who was building a house. He has one good eye, wonky reading glasses, grey hair, and the most amazingly high-pitched laugh that follows just about everything he says. He asked me where I was from. I told him Brisbane, Australia. “Ahhh, Brisbane,” he said. “I own two houses there. Hehehehehhe.” If I hadn’t been squatting on the ground I would have probably fallen off my chair. I soon learnt that many of the people here have lived in Australia, and that there are in fact more Penrhyn Islanders in Brisbane than on Penrhyn, and even more again in North Queensland. The people here understand what city life is like, and for that reason they appreciate their simple lives.

It took me a little while to get used to the fact that here you can’t just go to the shop and buy what you want or need. I once enquired about procuring one of the nice floral shirts the men wear. I was told that they’re all sewn by the women on the island, when the material arrives on the supply ship; they cannot be bought. Even the buttons are cut and drilled from pearl shells collected from the lagoon. Not long after my arrival, I could often be seen hobbling about the waterfront in my sea-softened, bare feet. Shortly after, I was very kindly loaned two very important items that have now made me a free man and a functioning member of society. The first item was a pair of ‘jandals’ (thongs/flip-flops), an essential piece of footwear for anyone wishing to assimilate into Island Life. The truth is, this is the first pair I’ve ever owned, so walking in them was something of a challenge at the beginning, however, I’m now bounding amongst the coconut palms like a natural. The second important item was a bicycle! The principal of the Omoka School kindly lent me hers while she went away for Christmas. Everyone here has a petrol bike they use to get around, walking any distance is unheard of. My bicycle ranks me somewhere between the kids on their bicycles, and the adults on their petrol bikes. Thankfully, being a small island, nothing is too far away. My bike is now my faithful companion, ferrying me to and fro, up and down the one road in Omoka, and sometimes down to the end of the air strip and back, if I wish to stretch my legs.

Penrhyn Islanders are devout Christians. Church is attended three times on Sunday, as well as twice during the week, and the sabbath is very strictly observed. Fishing, boating, swimming, even cutting the grass, are all outlawed on Sunday. As a matter of principle, I’m saying yes to every offer that comes my way, and am generally trying to involve myself as much as possible in island life. This fact, as well as the fortuitous timing of my arrival, means that I’ve really been very busy here, with all the church, singing, feasting, camping and fishing that has been going on, I’ve hardly had a day to myself, the adventure really hasn’t stopped.

My first CICC service will stay with me for a long time. Standing there, seeing everyone in their Sunday best, the women wearing their woven coconut fibre ‘rito’ hats, singing and wailing with all their hearts, was a truly moving experience. When we all sat down to hear the preaching in Māori I sat there in sublime bliss, looking out the windows to see the green palm fronds swaying against a perfect, cloudless blue sky, with the faint sound of waves breaking on the reef outside. I was filled with a sense of gratitude that I had landed at such a special place. A genuinely uplifting experience.

Part VI

My coming to Penrhyn marked the first international boat arrival since 2019, and even before covid it was very rare to have more than one or two cruising boats here at a time. Part of the formalities and paperwork I had to complete was the signing of the guest log, a task undertaken by every single yacht that has been here for the past 40 years. I pored over that logbook, reading the short notes left by previous sailors.

It was a late Friday afternoon when I arrived at Penrhyn. The following Tuesday was the Omoka School end of year prize giving ceremony. The 40 or so children sat boisterously on plastic chairs while dignitaries from the village made speeches. The men sat at the head of the shelter and were the ones to present the prizes to the best children of each cohort. Each child received their certificate, a cash prize, and a kiss on the head or cheek, depending on their height. The ceremony started with “Kia Orana, Hello Everybody, and G’daaayyy Maaaaate” much to everyone’s amusement, I laughed too, and nodded in appreciation. The principal later called me up to present awards to the three year-nine girls. I gave each girl their certificate and a kiss on the cheek. This caused the most tremendous sensation, young and old alike were in fits of laughter. I hope the sunburn disguised my red cheeks.

The speeches were in a mixture of Māori and English, laughter from the crowd was always preceded by Māori, not English. I did learn, however, that the Omoka school has a zero tolerance policy for swearing and back chatting, and that ‘traditional lunch Wednesdays’ were going well. There was kai kai (food) afterwards and I posed for many photos, adorned with my frangipani garlands and a flower headdress.

Part V

Today marked one month since my arrival. It also marked the end of the festive season here. This means, of course, there was a closing feast at the mission hall, as well as singing and dancing. Despite the length of my stay, I’m still regarded as something of an esteemed guest, and so I sat at a table at the head of the hall, accompanied by the Deputy Prime Minister of the Cook Islands, the Mayor, their spouses, as well as other important men and women of the Island. There were numerous plates of food: pork, chicken, taro, breadfruit, rice, pumpkin, etc. I was handed a ne mata (drinking coconut), and the feast began. We ate with our fingers and watched over the hall full of happy and smiling people who were likewise seated with a seemingly limitless supply of hearty food and drinking coconuts. The singing that followed was as spectacular and moving as ever, and at times everyone erupted in laughter at a particularly vocal solo, or an old man bounding from his seat, dancing like a youth, completely lost in the moment. As I sat there, with a full belly and my sides splitting with laughter, just like everyone else, it dawned on me just how at home I feel.

Each morning I rise, open the front door, the trade winds bowl in and the curtains start to dance. I look out over the blue lagoon and appreciate just how lucky I am to have ended up here, although, as I am often told, and am slowly learning, it wasn’t luck at all that set me ashore on Penrhyn Island.

A more perfect slice of paradise may not exist.

9th January 2023